Data and government openness: where next?

Last week, the Institute for Government published our Whitehall Monitor 2017 annual report, which uses open data to chart the size, shape and performance of government in the UK, including on transparency. In short, we couldn’t compile such a report without government openness, but there are some worrying signs for the future.

Our report wouldn’t be possible without the various commitments made by various UK governments to publishing open data. And it wouldn’t be possible without the help, support and advice of civil servants across government – in the analytical professions, in the new digital, data and technology profession, in the Cabinet Office, across departments and at the Office for National Statistics. These are the sorts of dedicated public servants who give up evenings and weekends to go to unconferences (like UKGovCamp or OpenDataCamp) to make government better.

But for all that vitality it’s not clear what direction the government is taking on open government at the moment – there was no UK ministerial representation at the recent OGP summit, for example. And our report found a few other warning signs.

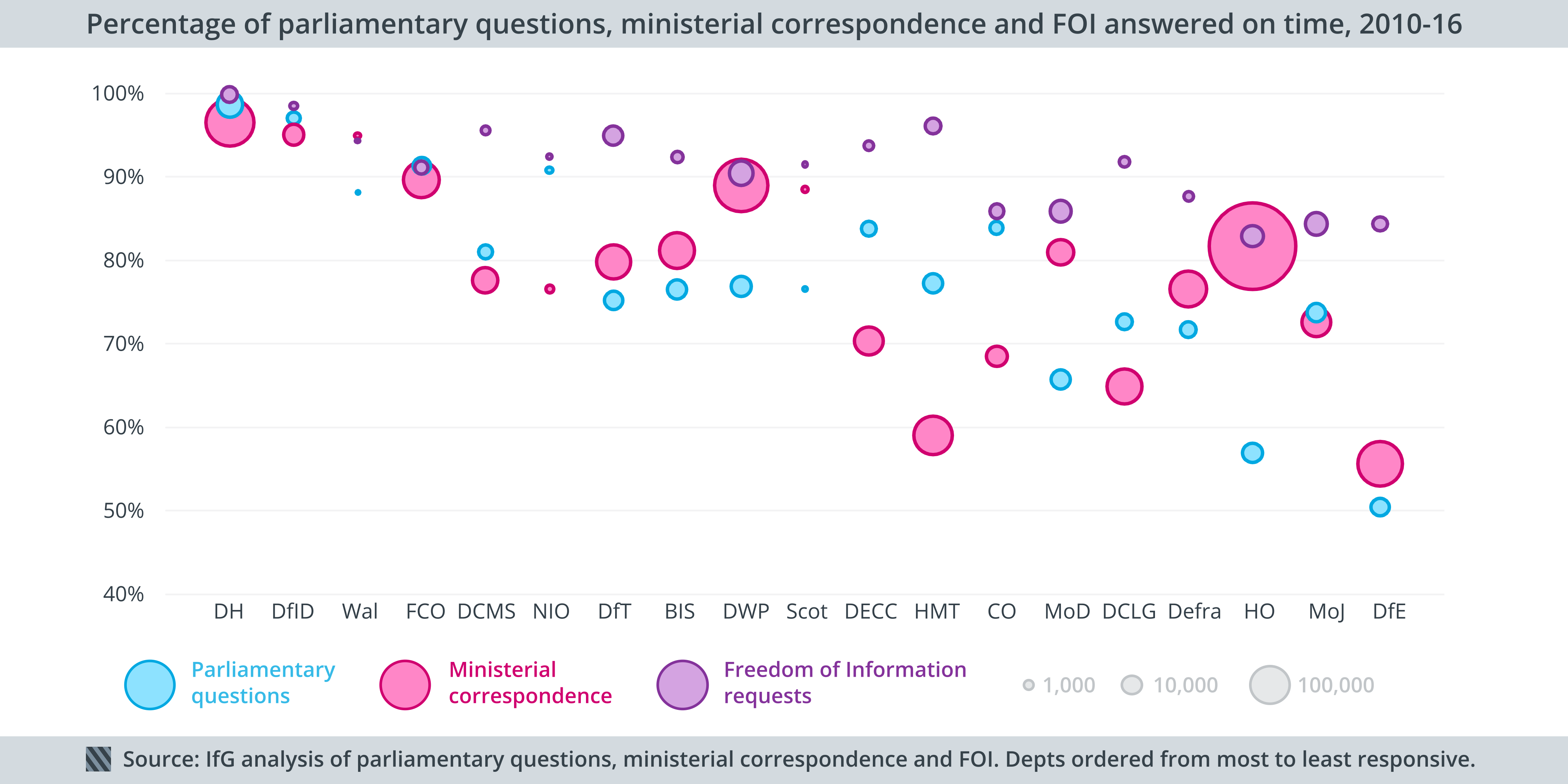

The Home Office under Theresa May had one of the worst records for replying to requests for information on time.

Between 2010 and 2016, the Home Office had the worst record of all departments in responding to Freedom of Information requests on time and the second-worst record in responding to written parliamentary questions on time. (It was a respectable mid-table on ministerial correspondence, despite receiving more than any other department.) Overall, the Home Office ranked third-worst, ahead of only the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and Department for Education (DfE). On FoI, those three departments responded to less than 85% on time in total between 2010 and 2016 – that would fall below the Information Commissioner’s threshold, underneath which departments can be subject to special monitoring.

Departments have become more likely to withhold information in response to FoI requests.

How quickly departments respond is a useful indication of departments’ administrative competence, but how much they release is a better indicator of their transparency. In response to FoI requests, departments can choose to release all the information requested, partially withhold it, or withhold it in full.

Between 2010 and 2016, departments went from withholding information in full in response to 25% of requests to 40% – from two in eight, to two in five. There may be good reasons for doing so – a number of exemptions are available, such as where personal data is involved – and some departments withhold more than others. But this general retrenchment on transparency is not encouraging.

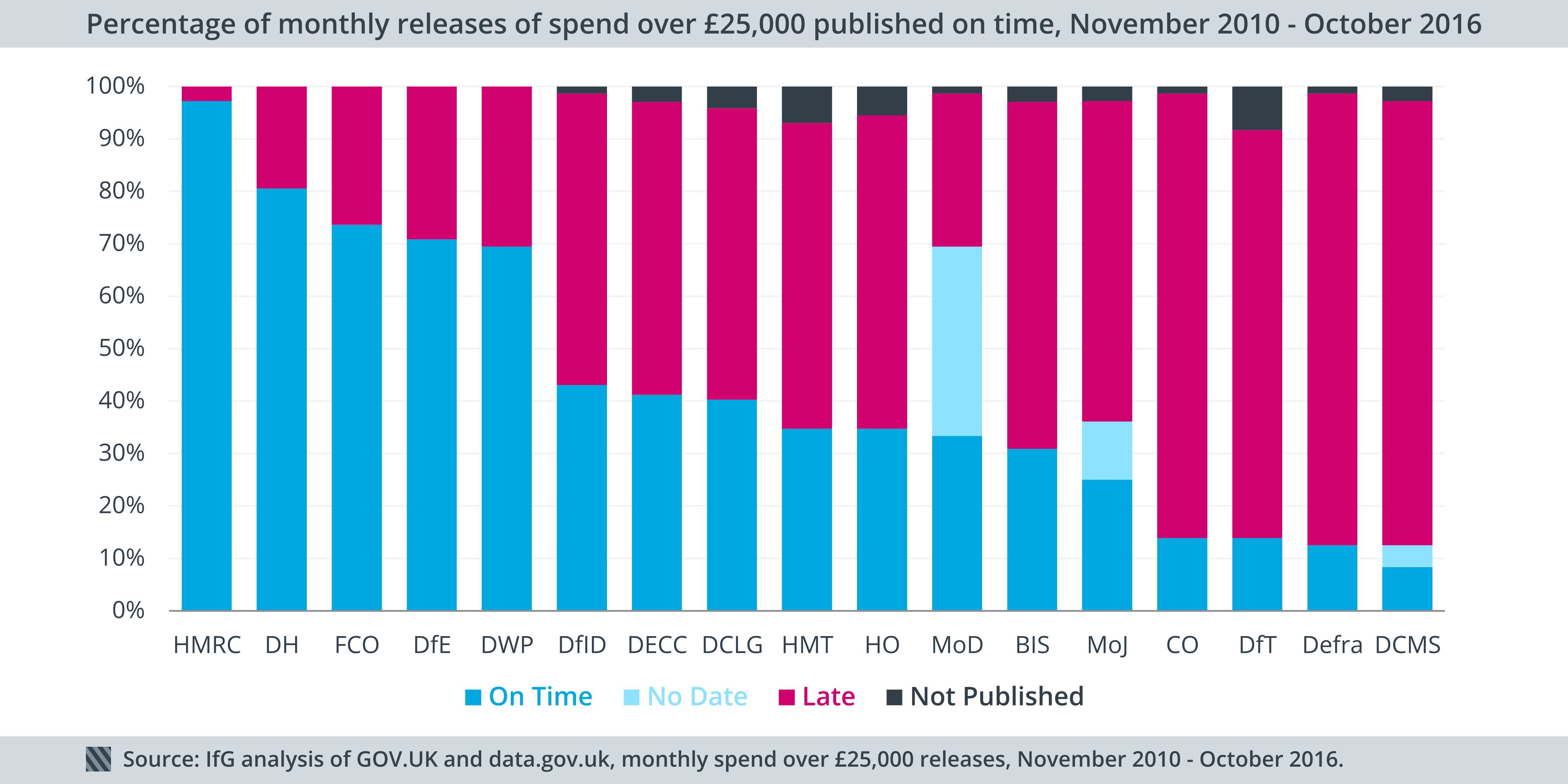

Departments’ record in publishing key datasets was patchy.

FoI is only part of the wider transparency landscape. Shortly after becoming Prime Minister in 2010, David Cameron wrote to all departments about the virtues of openness, and told departments to open up some key datasets, including contracting spend over £25,000 (monthly) and organograms (every six months).

Altogether, 51% of the monthly spend releases were published late (after the end of the following month), with 3% not published at all (more than 5% at DfT, HMT and HO). The Home Office again performed relatively poorly; between November 2010 and October 2016, 35% of its monthly releases were published on time. Just five departments – HMRC, DH, FCO, DfE and DWP – definitely published more than 50% of their data on time. The Cabinet Office, DfT, Defra and DCMS published under 20% of their releases on time, with the Cabinet Office infamously publishing some of its spend data 13 months late, only after FoI requests from the open data start-up Spend Network.

Publication has also tailed off in recent months, and there was no published spend for the new Departments for Exiting the European Union (DExEU), International Trade (DIT) or Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) by the end of 2016.

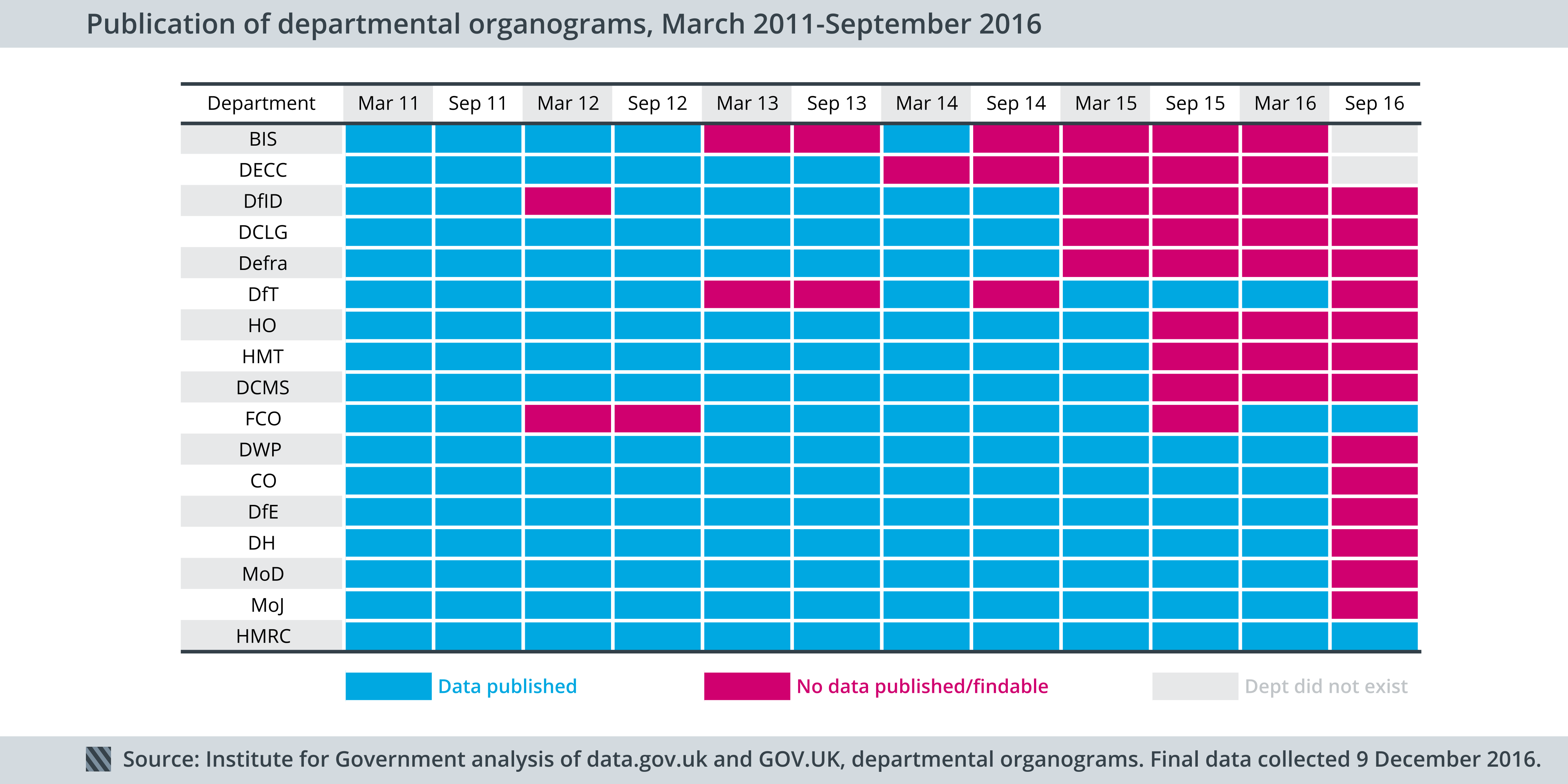

Departments’ records in publishing their organograms – detailed lists of employees, their pay and their seniority – are better, but still patchy in some cases and have worsened over the past couple of years. For March 2011, all departments published some data in some form; for March 2016, eight departments failed to publish any data. It’s worth noting that data.gov.uk has recently revamped its system for publishing this data, making it easier for departments to do so.

But what does this patchy publication tell us about government openness? It suggests that a letter from the (previous) Prime Minister mandating box-ticking terms isn’t enough to change a culture. But it also implies that this data isn’t being used by departments themselves to manage what they do. We need a culture where this data isn’t just being published (or not published) for the sake of it, but where data and openness are actually helping government improve its effectiveness and helping the rest of us to hold it to account.

Good work continues on data and openness within government – on everything from implementing the current National Action Plan, to Open Defra, to the Register Design Authority in the Government Digital Service. There are strong communities, within and outside government, championing data and openness. But all of us need some clear direction from government as to where data and openness are going next.